If we don’t make our sick people a priority we’re not a society

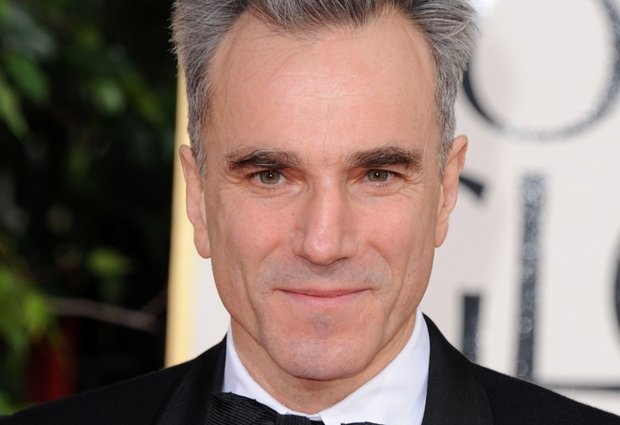

DANIEL DAY-LEWIS SAYS

The actor Daniel Day-Lewis has toured the site for a 12-bed hospice in Wicklow which he has worked on since his mother’s death.

Daniel Day-Lewis, who has a house in nearby Annamoe, is a supporter of the proposed facility, which will be located in idyllic rural Magheramore.

His mother, Jill Balcon, had chosen to end her days in a hospice instead of at home because she felt “safe and comfortable there”.

“Newborns, children, the sick, the disabled, the dying … if we do not make them a priority we have not right to respect ourselves as a society,” the actor stressed.

Personal: “As much as it is personal for us to have these facilities in Wicklow, it is also important for us to be doing things of value in this country when we are so often led to believe that the doldrums will finish us all off.”

The actor, who lives in Wicklow with his playwright wife Rebecca Miller and their two children, paid tribute to Columban Sisters for donating the site.

Evanne Cahill said the hope is that the HSE will include it in its 2014 service plan and pre-planning has been submitted to Wicklow County Council.

The “passion and professionalism” of Wicklow people determined to build a hospice inspired the Worldwide Ireland Funds to get involved in the project, president and CEO of the funds, Kieran McLoughlin, told the Herald. The Wicklow Hospice Foundation has just reached a crucial €3m target, with help from the funds.

The amount is the required half of the building cost which will trigger a commitment from the HSE to meet the second half of the cost. Donors to the American-Ireland Funds committed to an ongoing relationship with the project after an impressive address to the Funds annual Gala dinner in New York earlier this year by Daniel Day-Lewis.

Sligo, Yeats County finds it’s working capital in its couch cushions

Beautiful Sligo pictures of seaside, lakes and wild life at its best.

Money has to come from somewhere. During the boom years in Ireland, it came from bond investors, through Irish banks and into mortgages. That money’s gone. It could come from a government running a deficit, but the Republic of Ireland, still operating under the watchful eyes of the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission, doesn’t have that luxury.

Since the crash, the government hasfocused on foreign direct investment as a source of capital, with some success. This month Overstock.com(OSTK), for example, announced 45 new jobs at a software development center in Sligo, far from the tech hub of Dublin.

But this is not enough good news. It’s difficult, as an economist or a policymaker, to determine the exact difference between speculative investment and working capital, the loans that help businesses grow naturally to meet market demand.

But this is not enough good news. It’s difficult, as an economist or a policymaker, to determine the exact difference between speculative investment and working capital, the loans that help businesses grow naturally to meet market demand.

In Sligo, as elsewhere in Ireland and all over the euro zone, when the cheap money and the fast mortgages disappeared, so did all the working capital. Several business owners in the center of the city told me to ignore what I heard from Dublin. Banks are cranky and scared, they said, and credit is not to be had. The one new business on Bridge Street, a cell phone repair shop that opened this spring, bought stock and furniture with the owner’s personal savings.

This leaves the Sligo Chamber and the Western Development Commission with a problem. These are the agencies charged with economic development for the area. Economic development, even of good ideas, takes money. But there’s no money from Dublin for any ideas, good or bad. The Western Development Commission has 70 percent less money and 30 percent fewer employees than at its peak during the boom years. So the chamber and the commission have gone looking for capital, anywhere they can find it. And they have found it.

This leaves the Sligo Chamber and the Western Development Commission with a problem. These are the agencies charged with economic development for the area. Economic development, even of good ideas, takes money. But there’s no money from Dublin for any ideas, good or bad. The Western Development Commission has 70 percent less money and 30 percent fewer employees than at its peak during the boom years. So the chamber and the commission have gone looking for capital, anywhere they can find it. And they have found it.

Early in the 2000s, the European Union set up a venture capital fund for the west of Ireland, managed through Dublin. No new investments have been made through Dublin since 2010. In 2012, the Western Development Commission began turning its old equity stakes through the fund into new cash, then reinvested those in a new vehicle, the WDC Investment Fund. It’s targeted toward artists and artisans in the region, to help them with microloans to find markets abroad. (Among its first round of applications, the commission heard from all kinds of businesses—septic tank distributors, for example—desperate for working capital.)

In 2011, a group of volunteers calling itself “Team Sligo” found 60,000 euros in donations from local bars and retailers, paid for focus groups in Dublin, and used volunteer copywriters and PR professionals to create a marketing campaign for the city. This year’s effort, supported by 176,000 euros from the same local businesses and an EU regional development fund, has adopted the slogan “Sligo—Who Knew?” The city does not have working capital. But it does, it turns out, have a rich traditional music scene, truly stunning scenery, and an Atlantic-facing shallow beach with a consistent swell and overhead rollers. (Overhead rollers are good for surfing on.)

The city was also home to William Butler Yeats, one of the greatest poets of the English language.

What Sligo doesn’t have is a highway from Dublin, and the focus groups revealed that even the Irish had no idea what was up there in the northwest of their own country. Monday’s front page of Western People, a local weekly, reported that traffic to Knock airport had wildly exceeded expectations this summer from Frankfurt-Hahn and London Stansted airports. Sligo. Who knew?

What Sligo doesn’t have is a highway from Dublin, and the focus groups revealed that even the Irish had no idea what was up there in the northwest of their own country. Monday’s front page of Western People, a local weekly, reported that traffic to Knock airport had wildly exceeded expectations this summer from Frankfurt-Hahn and London Stansted airports. Sligo. Who knew?

“I’d be scared of a big wad of money,” says Paul Keyes, chief executive officer of the Sligo Chamber. “We need to get our structures in place.” Tourism promotion in Ireland used to have a national theme, with Celtic crosses and the generalized nostalgia the Irish call “diddly-aye,” run out of Dublin. But the tourists stayed in Dublin.

The recession, says Keyes, has forced Ireland’s west to find a message for the west. Barren. Lovely. Tuesday morning, I took a run along the ocean road, and an Audi with German tags pulled over to ask me a question. The driver, dressed in adventure gear, asked me whether I knew where he could find a grocery store. The money has to come from somewhere.

Four cups of tea is good for our liver function, researchers now find

A STUDY FOUND THAT INCREASED CAFFEINE INTAKE MAY REDUCE FATTY LIVER IN THOSE WITH NON-ALCOHOL FATTY LIVER DISEASE (NAFLD).

Seven out of 10 people diagnosed with diabetes or who suffer from obesity have the condition, and cases are rising.

There are no effective treatments for NAFLD except diet and exercise, reports journal Hepatology.

Professor Paul Yen, of America’sDuke University, carried out a study using cell cultures and mice models.

He found that caffeine stimulates the metabolization of lipids stored in liver cells and decreased the fatty liver of mice that were fed a high-fat diet.

The findings suggest that consuming the equivalent caffeine intake of four cups of coffee or tea a day may be beneficial in preventing and protecting against the progression of NAFLD in humans.

Prof Yen said: “This is the first detailed study of the mechanism for caffeine action on lipids in liver and the results are very interesting.

“Coffee and tea are so commonly consumed and the notion that they may be therapeutic, especially since they have a reputation for being “bad” for health, is especially enlightening.”

The discovery could lead to the development of caffeine-like drugs that do not have the usual side effects related to caffeine, but retain its therapeutic effects on the liver.

Howling wolves gives clue to who is top dog

Wolves choose to howl to maintain contact with each other, not because they are stressed

Wolves howl more when a close companion or high-ranking group member leaves the group.

That’s what scientists found when they analysed how captive wolves reacted when one was taken to the forest for a walk.

Known to be social creatures, the work further emphasises the importance of a wolf’s relationships within its pack.

The findings, published in Current Biology, suggest the wolf’s howl is explained by social factors rather than physiological ones such as stress.

Friederike Range from the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria, who co-authored the work said the wolves were communicating to each other just how important they were.

“We didn’t know there was some flexibility on how much they howl depending on their relationship. The amount of howling is really defined by the quality of the relationship.” Dr Range said.

She told BBC News that the wolves howled differently depending on which one was taken away.

Calling ‘friends’: The creatures call has long fascinated scientists and so unique are their howls that researchers can now recognise individual wolf howls from the wild.

Dr Simon Townsend one of the lead authors from the University of Zurich, Switzerland, said that wolves could be using the howl in a strategic way to regain contact with dominant individuals or with friends.

“Wolves seem to howl more when higher ranking individuals leave because these individuals play quite important roles in the social lives of wolves.

“When they leave it makes sense that the remaining wolves would want to try and re-initiate or regain contact. The same applies for friendship.”

Stress-free wolves: The team listened to the howls of nine wolves from two packs in Austria’s Wolf Science Center and they observed that when a wolf was only taken away to a close surrounding area – rather than the much further away forest – their companions did not howl.

The study was done in a captive setting which enabled the team to measure the wolves’ underlying physiological stress by analysing the cortisol levels in their saliva.

“What we expected was higher cortisol levels if the wolves were more stressed when ‘friends’ leave, but what we found is that cortisol doesn’t seem to explain the variation in the howling behaviour we see,” Dr Townsend told BBC News.

“Instead it’s explained more by social factors – the absence of a highranking individual or the absence of a closer affiliate.”

Holly Root-Gutteridge, a wolf-howl specialist from Nottingham Trent University, UK, who was not involved with the work, said the study was “exciting for wolf scientists”.

“The wolves are choosing to howl because a preferred wolf has been removed and they appear to consciously choose to stay in touch with that wolf. That’s fascinating because it’s really hard to separate social contact calls from the trigger causing them and also the hormone change the trigger causes.

“It means the wolves may be taking complex social interactions into consideration and then changing their own behaviour accordingly, not by instinct but by choice,” Ms Root-Gutteridge told BBC News.

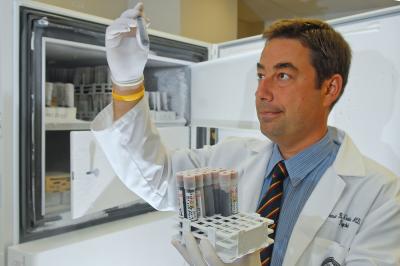

Predictors of suicidal behaviourfound in patients’ blood

Changes in gene expression can indicate heightened risk for self-harm.

People who are intent on taking their own life may not seek counsel or discuss their thoughts with others. Having some ways of predicting the rise of suicidal thoughts could help save at least some of the 1 million people worldwide who die that way every year.

“It’s a preventable tragedy,” says Alexander Niculescu, a psychiatrist at an Indiana University in Indianapolis who is looking for biological signs of suicide risk.

Because of the brain’s complexity and inaccessibility, the search for predictors of suicide risk has instead focused on molecular signs, or biomarkers. These biomarkers help to indicate which people are at even higher risk. Niculescu and his colleagues have found six such biomarkers in blood that they say can identify people at risk of committing suicide. Their work is published in Molecular Psychiatry1.

The study by Niculescu and his colleagues had four distinct phases. First, they identified nine men with bipolar disorder from a longitudinal cohort study at Indiana University who, between visits to the lab, had switched from having no suicidal thoughts to scoring highly on a suicide-risk scale. They looked for changes in gene expression in men’s blood cells, and identified candidate biomarkers. These biomarkers were then checked against previous work on genes related to mental illness and suicide to identify 41 most likely to be involved. “It works like a Google searchranking,” says Niculescu. “Those that had the most independent lines of evidence got the highest rank.”

Next, the researchers checked their results against blood samples taken by the coroner from nine men who had committed suicide. This enabled them to narrow their list of candidate biomarkers from 41 to 13. After subjecting the biomarkers to more rigorous statistical tests, Niculescu’s team was left with six which they was reasonably confident were indicative of suicide risk.

To check whether these biomarkers could predict hospitalizations related to suicide or suicide attempts, the researchers analysed gene-expression data from 42 men with bipolar disorder and 46 men with schizophrenia, and found correlations with four of their biomarkers, especially in the bipolar group. This indicates that the active genes are not just ‘state markers’ of immediate risk but ‘trait markers’ that can indicate long-term risk. When the biomarkers were combined with clinical measures of mood and mental state, the accuracy with which researchers could predict hospitalizations jumped from 65% to more than 80%.

The strongest predictor was a biomarker encoded by a gene called SAT1. “It was head and shoulders above the rest,” says Niculescu. The work “opens a window into the biology of what’s happening,” he says.

Ghanshyam Pandey, a psychiatrist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, says that Niculescu’s work is an important step in the search for psychiatric biomarkers, but the small sample size means the results will have to be validated in much larger groups and tested for specificity and sensitivity before the results could be used clinically. “That’s a big challenge,” Pandey says.

Niculescu says that this type of work is usually done with much larger sample sizes but that he and his colleagues used rigorous, multi-step methods to weed out false positives. The next step, he says, is to look at the levels of these biomarkers in the general population and in other at-risk populations, such as those with depression or suffering from stress or bereavement. “Suicide is not just related to mental illness,” he says. “It’s a very complex behaviour.”

The story of Ryan the chimp: The triumph and depression of a very lovable animal

Ryan the chimp contemplates a pinecone treat covered in peanut butter, sunflower seeds, and dried fruit.

Most of Save the Chimps’ residents have heartbreaking stories of suffering—and equally heartwarming stories of recovery. But some chimpanzees just get to you. Maybe you feel an inexplicable connection to them because their stories are a little sadder or because they found it harder to heal. For me, Ryan is one of those chimps. Whenever I see Ryan on his island, I think of the day I met him: the day he fell, and gotback up again.

Ryan was born November 17, 1987 in New Mexico to his parents Olivia and Doug. Before his second birthday, Ryan was shipped off to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, where he would reside indoors for 14 years.

Ryan had it tough at the CDC. He lived alone in a cage that provided just 25 square feet of floor space and five feet of height. Ryan also had to endure invasive experiments that required numerous liver biopsies; he even had part of his liver removed. All these needles and surgeries caused Ryan to develop physical scars that riddled his internal organs, but the damage went even deeper.

When Ryan was seven he began mutilating himself. He pulled out hair, hit his face, bit his ankles, and rubbed his knuckles raw. His laboratory caregiver, who tried desperately to comfort him, noted that he was depressed and withdrawn. Despite this, he was used in additional protocols. One study caused frequent vomiting and he lost 20 pounds. During another he developed an infection in the needle tracks in his forearm.

In 2003, Ryan’s life changed dramatically when he was retired to Save the Chimps. Although Ryan lived at the CDC, he belonged to The Coulston Foundation, a research lab in New Mexico. Save the Chimps took over Coulston and gained custody of Ryan. Ryan moved back from Atlanta to New Mexico, where he would meet other chimpanzees before moving to our sanctuary in Florida.

My first impression of Ryan was of a gangly, awkward, bewildered chimp. When Ryan arrived, the only space available was in the building we called “The Dungeon.” But for Ryan, the Dungeon was paradise. He could go outdoors and feel the sun on his face, a sun he had never seen. The measly 120 square feet of space was nearly five times the amount of space he had known. For the first time, he could climb.

That’s when Ryan fell. When he entered his new home, it was apparent he had never climbed before. But climb he did, shakily venturing up ten feet. Once he was there, he had no idea how to get down. He hung from the top, considering his options. We gasped as he let go and dropped to the floor. He got up and took a few cautious steps. His ankle was sore, but otherwise all was well. Although concerned, we rejoiced. Ryan had climbed. Yes, he fell, but he got back up again. And he bravely kept climbing until he was as agile as any other chimp.

Ryan’s recovery from isolation and trauma took nearly five years. Medications were required to help Ryan stop injuring himself. His long rehabilitation was a partnership between his caregivers at Save the Chimps, who never gave up on him, and Ryan himself, who never gave up.

Meeting other chimps was a challenge for Ryan, who didn’t understand how to navigate chimpanzee society. We kept trying to find companions for Ryan. Ryan kept trying too—over time he learned how to communicate, play, and groom others. Incredibly, Ryan ended up in one of the largest groups at Save the Chimps, Freddy’s Family.

When Ryan moved to his home in Florida, it was like nothing he had ever seen. Outside his new airy building was a hilly, three-acre island, complete with a covered bridge. Ryan had never lived anywhere but in a cage, and had never set foot on grass or sat under a tree. Would he be brave enough to walk out into this big new world?

We were so proud of Ryan, because he was and he did! It was a beautiful, breezy November day, and Ryan courageously went outdoors and into a new chapter of his life. Today, he goes out onto his island without hesitation, roaming with his friends, looking for goodies scattered in the grass. He’s even become a mediator, stepping in to stop any family disputes. He is often found next to Freddy, grooming him intently.

Ryan has gotten his happy ending, and we are grateful that no more chimpanzees live at the CDC. But there are hundreds of chimps in other labs waiting for their chance to retire. Among those behind closed doors are Ryan’s sister Chauncy and brother Martin, who are owned by the U.S. government and may reside at the Alamogordo Primate Facility in New Mexico. Two recent developments may spell a brighter future for Ryan’s siblings and other research chimps.

First, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed a rule to declare all chimpanzees endangered. Since 1990, chimpanzees have been “split-listed,” meaning that wild chimpanzees are considered endangered, but captive chimpanzees are not. Chimps are the only species with this designation. (Gorillas, for example, are considered endangered whether in the wild or in a zoo.) This split-listing allowed Ryan to be harmed in biomedical research.

If all chimpanzees had been declared endangered in 1990, it would have been difficult to scientifically justify using Ryan in invasive research. He would have been spared years of agony. You can help spare Chauncy, Martin, and other chimps from future harm by submitting comments to the government by August 12 to support the proposition to make all chimpanzees endangered.

Second, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently announced that they would retire all but 50 of their 360 chimpanzees. This means that Chauncy and Martin could be retired to a sanctuary, just like Ryan was ten years ago, as long as they are not among the 50 unfortunate chimps picked to stay in research. Save the Chimps and our fellow members of the North American Primate Sanctuary Alliance (NAPSA) are willing to work with the NIH to provide sanctuary for all of their chimpanzees. You can help by letting your Senators and Representatives know that you support the retirement of chimpanzees to sanctuaries.

When we compare the Ryan who first came to us to the Ryan of today—confident, relaxed, and friendly—it’s like they are two different chimps. But the Ryan we know and love today was always there, just waiting to be freed from his desperate situation. He proves that what the late Save the Chimps founder, Dr. Carole Noon, said was true: “All they need from us is a chance. If we meet them halfway, give them space and freedom, then they recover on their own.”

No comments:

Post a Comment